A CURRENCY is a wonderful flagship for a country, bobbing away minute by minute on the waves of global sentiment and trade. It is a useful proxy for where the market and economy is heading next, but in Zimbabwe’s case it has become more like an albatross around the necks of its leaders, dragging them further into an abyss of economic disaster.

Zimbabwe had to abandon its currency — hard won via bloody civil strife for freedom — in 2009 as effectively worthless, with the US dollar and rand being accepted instead as the main legal tender.

While this change did put a plug in runaway inflation, a new plank in the strategy has been to look east by accepting the Chinese yuan, Japanese yen, Indian rupee and Australian dollar as legal tender too.

The jury is out on how clever all of this is, as the ultimate aim should surely be to reclaim your flag — your currency in this case — and let it proudly flap away in the winds of global economic change.

My son, aged five, got into trouble during the recent heavy rains in South Africa when he left my iPad exposed to the elements after forgetting it on the lawn. I was, of course, furious (I use it for work, not only games), but he came up to me once the dust had settled with a Z$20m bill his grandfather, who is prone to going on safaris into deep, dark Africa, had given to him to pay. He’d heard an iPad cost about R5,000 or so, and thought the money would easily pay for it.

Of course, his attempt to solve one of the first bad experiences in his young life warmed everyone’s hearts — and we thanked him profusely for the largesse. But I did quickly explain to him that this money came from Zimbabwe, and was no longer in use because their economy was not like ours, or most others. It was certainly nowhere close to his German grandfather’s economy, which used the euro, of which each one was worth R15 and a whole lot more than the millions of Zim dollars he was so keen on parting with to settle his damages.

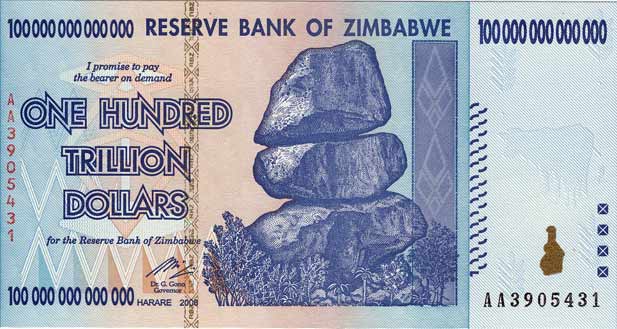

It is a sad state of affairs when a country can fall into a state of such disrepute — even sadder when it is on our doorstep. Of course, letting things slide so badly — it was so bad in Zimbabwe that the value of its citizens’ money was halving every day, and Z$20-trillion was worth just one US dollar — has serious repercussions. And there is no worse repercussion for a country and its elected leaders than when people begin to starve.

While Zimbabwe’s politicians have been running around looking for food import deals with South Africa to help stem a new food crisis as 2-million people need food assistance, the United Nations’ (UN’s) World Food Programme says money is a problem. The UN’s own plan to feed 1.8-million Zimbabweans is running into money trouble — it is $60m in the red and desperately looking for donors.

Of course, there is no reason Zimbabwe can’t become a breadbasket again — it has the land and resources to do it. But the system of land grabs has turned everything into a mess. Investors need to be brought in, and they’ll only do so if property rights are protected — if they know they are dealing with people who have the rights to farm the land. So, unfortunately, it’s over to the politicians again, who seem to forget that their future, and that of the starving millions, hinges on the economy. Running off to South Africa or adopting the yuan is not ultimately going to help.

Setting up two fairly simple programmes may be better. Start with a foundation of private property rights protection, as it is the clarity over property titles that is holding back investment. Then set up a programme to drive smallholder farming. To do this, go back to the basics — it needs an efficient market of buyers and sellers. Then there will be no more need to import hundreds of thousands of tons of maize. With these things on track, you can fly your economic flag — your currency — proudly again.

A top UN food man I spoke to said the UN would be only too keen to help set up such a market, but what is lacking is the political will. The Southern African Development Community also tells me it has a four-year plan in place to beef up food security, which includes Zimbabwe. But, again, all indications are that more input is needed from the Zimbabwean government.

Investment Asset Management’s Zimbabwe expert, Roelof Horne, says ultimately any country would want to have its own currency again at some stage as it formed a "shock absorber". Other currencies are driven by their own monetary policy and could be misaligned to your needs.

A looming problem is the need for even more money. The Zimbabwean government has agreed to a 26% pay increase for civil servants — which is hardly affordable. Its government bond market is not working well either — you need your own money for that — and so the country is battling to borrow externally.

The whole mess has led to a general lack of market liquidity, with banks short of funds, capital and deposits.

It is giving rise to talk of a possible relaunch of the Zim dollar, but the timing is out. To relaunch it, they will need high levels of confidence in economic policies. The value of a currency is determined by confidence, which is nowhere on display. According to Horne, should the currency be launched now, it will be a decision "doomed to be a failure".

"It is probably bound to lose value very quickly as people have no confidence," he tells me.

The solution is to get working on solid economic policies. Look to Asia as an example — using their currencies is not the solution, but their models, when implemented, would help set up the foundations for a booming food or cotton trade. Until then, Zimbabwe’s basket-case status remains in play, its currency doomed to the sidelines of the daily market news pages.

When TelOne started billing customers in US dollars back in February 2009, it was accused of having converted Zimbabwean Dollar bills to US dollars at unrealistic exchange rates resulting in ridiculously high bills which subscribers failed to settle.

When TelOne started billing customers in US dollars back in February 2009, it was accused of having converted Zimbabwean Dollar bills to US dollars at unrealistic exchange rates resulting in ridiculously high bills which subscribers failed to settle.